It is an improbable story. Forty years ago, teacher George Emeny was running a study hall from his dormitory apartment when a boy asked him to proofread a history paper. Three weeks prior, on February 27, 1973, members of the American Indian Movement, with the help of local Oglala Lakota (Sioux) occupied the town of Wounded Knee, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. The student’s paper attempted to address the resulting stand off with U.S. Marshalls. Reading the paper, George—who had spent childhood summers hunting, trapping minnows and building canoes with the Athabascan people of central Canada—was struck by the student’s inability to capture the true angst of Native existence. “I went to [Head of School] David Fowler and asked to teach a term of Native American history,” he recalls.

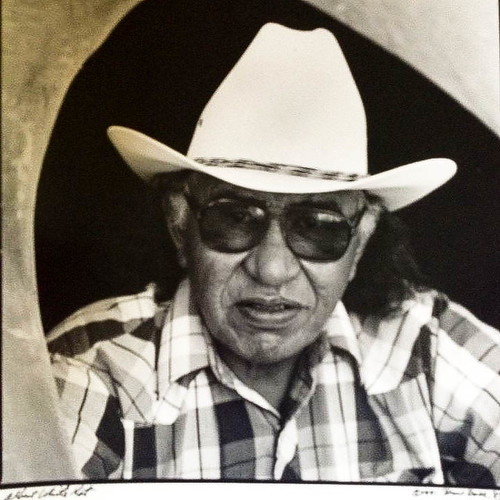

What followed is testament to the power of vision, commitment and passion. Aware of his own limited experience of Native cultures, George spent the next eight summers studying with Lakota professor Albert White Hat at

Sinte Gleska University (the first tribal-based university in the United States) in Mission, South Dakota. Albert was more than a language professor. He was a spiritual mentor, and--perhaps more than any man--preservationist for Lakota Sioux culture, philosophy and ways that had been illegal under United States law for more than a century.

Given Albert's upbringing--in a home in which he spoke only (officially banned) Lakota until the age of seven, and eventually schooled at one of the Jesuit boarding schools established to teach Catholicism and "American ways" (!), it is hard to fathom his openness and kindness to a prep school teacher from New Hampshire, yet he saw in George Emeny a man who was earnest, open to possibility, and who believed in Proctor. Albert accepted George's invitation to come to Andover, New Hampshire to teach us the ways of the Lakota. Below, from right, Albert White Hat, his adopted cousin John Around Him, George Emeny and dancers prepare a demonstration next to Slocumb Hall.

Albert came for a whole term as a visiting professor, but words like "professor" can not truly capture Albert's presence on campus, because Albert was not professing. He was being Albert White Hat, a man whose name in his native language "Wapaha Ska" means "White War Bonnet." He was being Lakota, and teaching by being. He lived in a universe in which all people and all things are both related and equal. At Proctor, he was engulfed by students and teachers who absorbed his subtle teachings with awe, respect and reverence. History teacher Bert Hinkley emerged as a campus leader who--with George Emeny, and with the eager support of David Fowler--maintained the values and philosophy that were Albert's gifts when he was back on the Rosebud Reservation. Below, the opening march of a pow-wow that drew Native Americans from across the Northeast to Proctor around 1990.

During his extraordinary career, Albert was criticized by some for sharing his teachings and opening traditional ceremonies to non-Native peoples. Yet he proceeded with confidence that this was the best course. He taught us to conduct inipi (sweat lodge purification ceremonies) at a remote corner of campus; he offered a welcoming statement at a Comencement in Lakota language and he sent three of his children to Proctor: Jacqui '87, Emily '94, Albert Jr. '00 (known to us as "J.R.") His grandson, Mark, will be a senior at Proctor this year. Below, from left, Emily '94, Mark, '14, George, Albert and their tour guide Aaron Thomas '11, taken three years ago.

Albert beacme a Trustee of Proctor Academy in 1989, and was an Honorary Trustee until his death last week. This role brought him back to Proctor repeatedly to emanate his calm, wise, humorous way of experiencing the world.

It's impossible to quantify Albert's impact on Proctor, but it is safe to say that we moved to become wiser, kinder and more appreciative of the interconnectedness of all things through him. These qualities will endure.

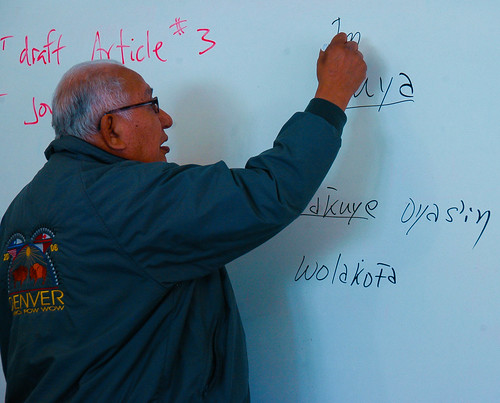

Below, he addresses the community in one of the most memorable and impactful assemblies I ever experienced.

The anthropologist Margaret Mead observed, "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it is the only thing that ever has." Albert White Hat changed this world for the better. He receive the Governor's Award in 2007; the Living Indian Treasure Award; the Gamahiel Chair for Peace and Justice in 1987; the Outstanding Indian Educator Award in 1995, and the National Indian Education Association's Indian Elder of the Year in 2001. We will remember him the way we remember a relative, for we are all related. Below, he teaches the concept of

mitakuye oyas'in: related to all things.

Listen as Albert reflects on his transition as a youth from anger to forgiveness:

Vision Quest

Albert authored books on

Reading and Writing the Lakota Language and--just one year ago--on

Zuya - Life's Journey. Now his journey reunites him with all his relatives who have gone before.

"Nake Nula Waun – I am always prepared, anytime, anywhere, for anything."