In 1927, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg upset the scientific world when he declared his eminently provable "Uncertainty Principle": the more you know about the location of something (like a subatomic particle,) the less you can possibly know about its trajectory and momentum.

It gets worse. The skeleton in the closet of quantum physics--sometimes called

The Quantum Enigma--is that observation of a particle by a conscious mind changes the nature of the particle. Light, for example, exists as "wave functions" in a state of virtual

probability until

observed by you or me, at which time it actually becomes a particle (photon). Our observation changes the reality we observe. It makes no sense at all, but it is tested to be true repeatedly.

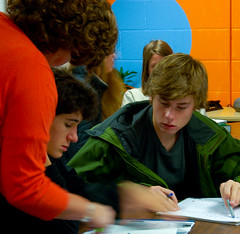

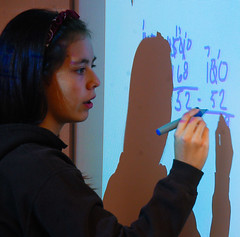

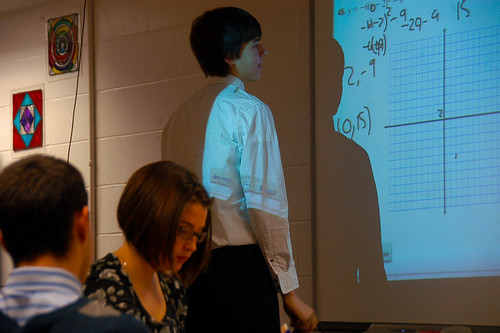

For most of us, truly understanding quantum physics is not a realistic goal. The more we study the sub-microscopic, the more we share the pursuit of cosmologists who look back in time at the origins of the universe. But let's transition to academics. Our "observation" is of student behavior, and the process of grading students bears similarities to scientific measurement (which it pretends to be.)

Let's consider

testing, which is a very close cousin to scientific experimentation. Few teachers are trained experts in assessment theory, yet we craft quizzes, tests and exams with little or no objective proof of their validity. That can be OK. The tempting trap is reliance on "one right answer" assessment: multiple choice items, fill-in-the-blanks, and anything that tells kids, "Your grade is the product of the number of correct answers." The problem is that we learn best in environments in which mistakes and imperfections are welcome as opportunities for greater insight and realization. Check out Diana Laufenberg's take in this TED address:

How to learn? From Mistakes.

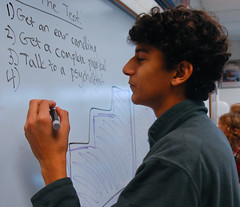

The answer, Laufenberg argues, is to keep education

experiential: pose questions and problems; listen to student voices, and encourage peer assessment of projects that never pretend to be perfect.

Unlike quantum physics, this is simple. The cosmological universe strives more for symmetry than for perfection. Being "right" and answering correctly have their virtues, but the best education challenges and empowers students to

speak, act, and

goof up.

Technically, winter arrived last Tuesday. But it was this Monday that we finally experienced our first snowstorm, with a foot of wind-blown white stuff. The first thing to do is go camping overnight at The Cabin! Below: Andrew Barban '02, Andrew Will '00 and Alex Estin '83.