The folks I follow on Twitter tend to be in education and social media, so when Sunday's

New York Times featured an article by Matt Richtel entitled,

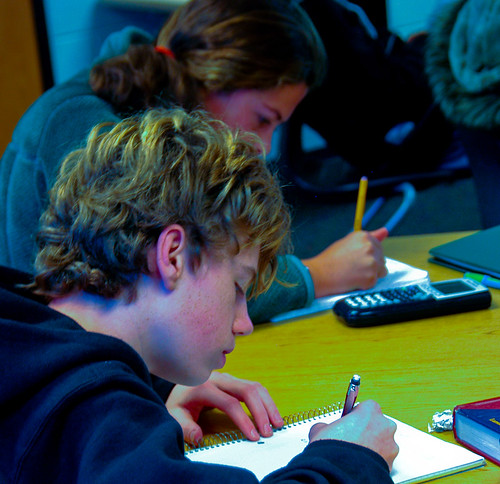

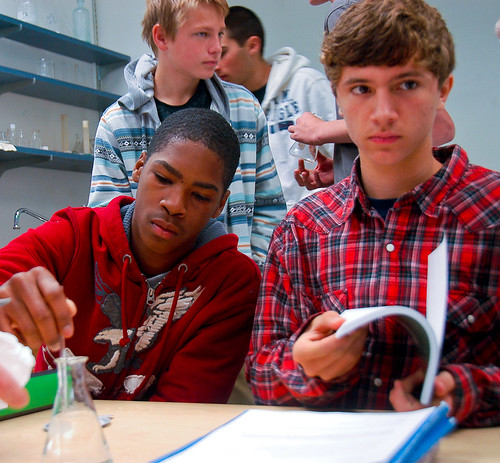

Growing Up Digital, Wired For Distraction, my Tweetdeck chirped with activity. The article is an alarming, depressing tale of bright, underachieving Silicon Valley high school students preoccupied by Facebook, Youtube, texting and gaming. The school principal is fighting fire with fire, investing in more technology to compete for students' attention in classes. Unintentionally, this piece should be a boon for boarding schools, where structures, schedules and supervision combat tech abuse as well as imaginable.

We are introduced to Vishay, a seventeen-year-old aspiring film-maker who acknowledges the distractions of social media. He doesn't do his homework and is gambling on the quality of his film-editing skills (learned on Youtube) for college admission. His parents set him up with a high-end laptop to encourage his talents and stave off depression. That kind of permissive parent-child relationship is cleaned up in a boarding school environment.

What I find maddening is the sense of despair suggested by a world in which technology strips kids of attention spans, and there's nothing we can do about it. It's the kind of "ain't it awful" thinking that drives me nuts. There are things we can do, and they are not limited to residential schools (despite the advantages of 24/7 environments.) Another article in the

Times this week, authored by Virginia Heffernan, questions the etymology of "attention span." In

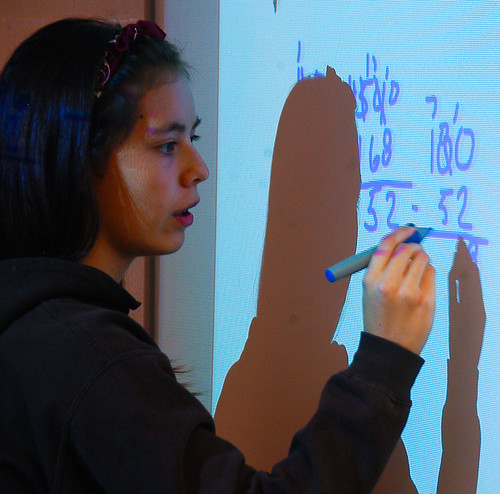

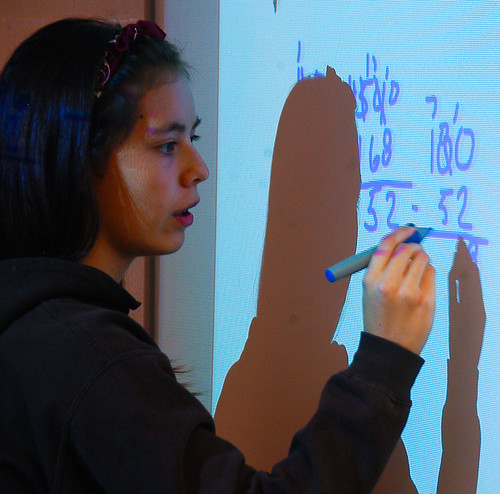

The Attention Span Myth, Heffernan observes that it is "the content of activities" (I would add the dynamism of teaching methods) that wins our focus.

In the 1870s, Americans chuckled knowingly at Tom Sawyer's distractibility during a sermon, yet today we expect teenagers to sit quietly in long classes and attribute their agitation to a new social disease.

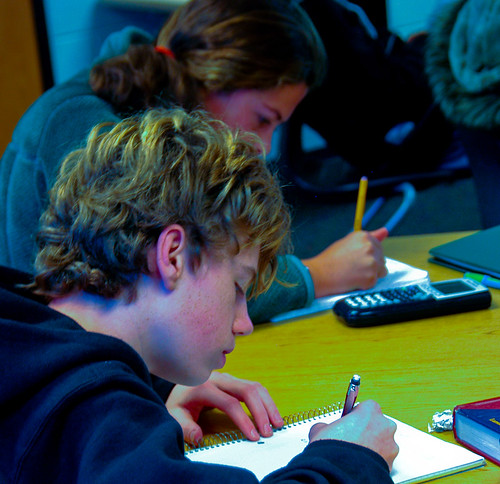

In the seventh grade, I had a terrific attention span in math class, as I day dreamed I was Carl Yastrzemski. I could go on and on...making tumbling catches, throwing runners out at the plate, smacking fastballs inside Pesky's Pole....all while a truly uninspired teacher demonstrated long, long division on a chalkboard. I did terribly in math that year, but--in retrospect--do I regret the thrill of those game winning home runs that helped me survive?

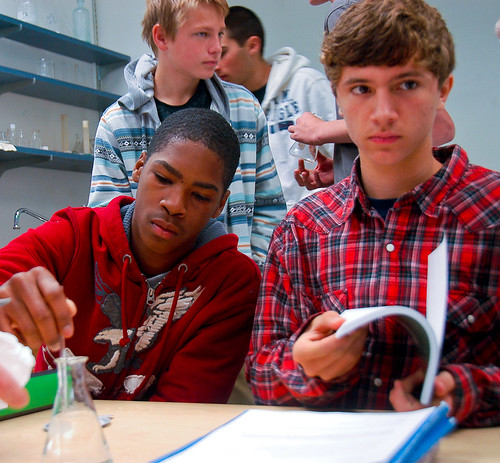

It has been observed that nineteenth century schools did a good job of preparing people for factory work. You learned to sit still and perform repetitive tasks. We also know that the world's great thinkers (Kepler, Edison and Einstein, for example) struggled with traditional structure and worked with almost obsessive intensity on projects of their own choosing.

I could go on, but I have to check my Tweetdeck, my Facebook status, email and then download some tunes.